Battling Bent Blood Cells

Progress in Sickle Cell Disease

With every beat of your heart, blood carries oxygen from your lungs throughout your body. This life-sustaining process happens automatically, whether you’re awake or asleep.

But for people with sickle cell disease, it often goes awry. People with this disease have an abnormal type of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying molecule in red blood cells.

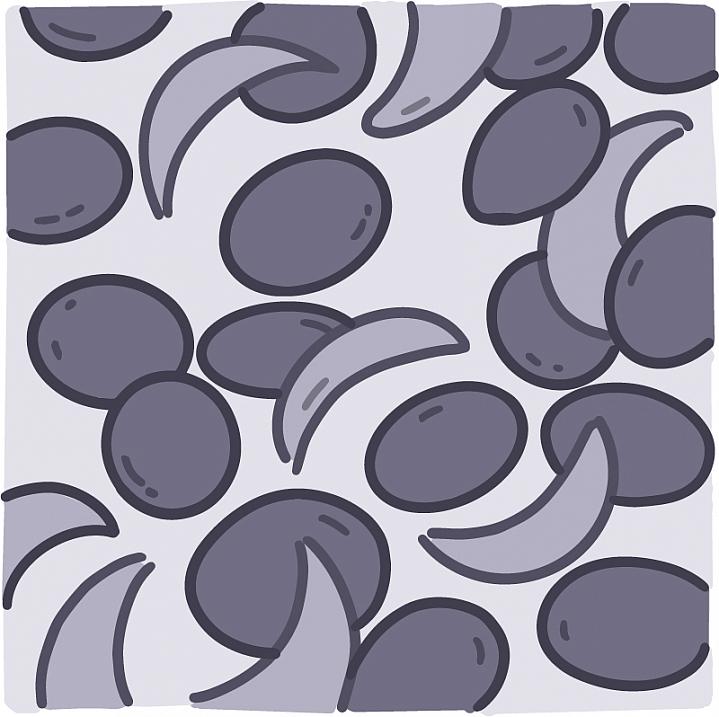

Normally, red blood cells are flexible and shaped like a disc. But the hemoglobin in people with sickle cell disease causes abnormally shaped red blood cells. Most commonly, they’re a crescent (or sickle) shape.

These inflexible, bent cells can stick to the blood vessel walls. The resulting clumps slow or stop the flow of blood. This may lead to pain and organ damage.

“Sickle cell disease can potentially block blood supply to any organ in the body,” explains Dr. Swee Lay Thein, a blood disorder expert at NIH.

Most people with sickle cell disease used to die before reaching adulthood. But with modern treatments, people in the U.S. now live into their 40s, 50s, or even 60s. And researchers are working on cutting-edge therapies, such as fixing the broken geneA stretch of DNA you inherit from your parents that defines features, like your risk for certain diseases. that causes the disease.

“I think treatment is going to look very different in the next 20 years,” says Dr. Allison King, an expert on sickle cell disease in children at Washington University in St. Louis.

One Gene, Many Symptoms

Sickle cell disease is caused by changes in a single gene. But everyone has two copies of the gene. You inherit one copy from each parent. More than two million people in the U.S. carry one abnormal copy, called sickle cell trait. They don’t usually have any symptoms. But if you inherit two copies, the result is sickle cell disease.

About 100,000 people in the U.S. live with sickle cell disease. Most are African American. But every baby born in the U.S. is tested for sickle cell disease at birth. This helps doctors start treatment as early as possible.

Children don’t usually show symptoms until they’re between six and 12 months old, Thein explains. Babies’ red blood cells have a different type of hemoglobin, called fetal hemoglobin. As they grow, the body switches to producing adult hemoglobin. Then, the sickling cycle begins.

A normal red blood cell lives for around three to four months. But in people with sickle cell disease, the cells usually live for just two to three weeks. This leads to anemia, a condition in which your blood has low amounts of red blood cells or hemoglobin. Anemia lowers oxygen in the body, which can cause fatigue, dizziness, and headaches.

Pain is another common symptom. It can be so severe that people end up in the hospital. These pain episodes are called a “sickle cell crisis.”

“People’s lives are disrupted by these episodes,” says Thein. “For children, that means missing school. Adults might miss a lot of work.”

Blocked blood flow to the brain can cause strokes, even in children. Strokes and clogs in the blood vessels in the lungs are some of the most dangerous complications of the disease, Thein says.

New Drug Options

The most common treatment for sickle cell disease is a drug called hydroxyurea. It coaxes the adult body to make fetal hemoglobin. This increases the number of functional red blood cells.

Hydroxyurea doesn’t work for everyone. But three new treatments have been approved in the last few years. Some of the newer drugs prevent sickled cells from sticking to the blood vessels.

Thein’s team is testing a drug to stop blood cells from bending in the first place. “That would be the most effective thing—to stop the sickling process,” she explains.

Even though drugs help many people, taking medication daily can be hard, King explains. Low levels of oxygen in the brain in people with sickle cell disease can affect memory. King and her colleagues are testing ways to use technology, such as smartphone apps, to help people take their drugs as prescribed.

Some people with sickle cell disease may need to have regular or emergency blood transfusions, in which they receive donated blood.

Fixing the Blood Cells

Currently, the only cure for sickle cell disease is a bone marrow transplant. Bone marrow is the spongy tissue containing the stem cellsImmature cells that have the potential to develop into many different cell types in the body. that give rise to blood cells.

In a bone marrow transplant, the stem cells in the patient’s bone marrow that produce blood cells are first destroyed. Then, stem cells from a donor without sickle cell disease are transferred into the patient. These new stem cells will produce blood cells that don’t sickle.

The procedure is risky. It’s considered too dangerous for adults. But the main problem, explains Dr. Matthew Hsieh, a transplant researcher at NIH, is that most children don’t have a matched donor. If certain proteins on the donor’s cells are different than the child’s, the transplant can fail.

Hsieh and others have developed new methods to transplant bone marrow from people who aren’t a perfect match. They’re also developing ways to prepare the bone marrow for a transplant that could make the procedure safer for adults.

Researchers are also testing an approach called gene therapy. In gene therapy, a patient’s own stem cells are collected. Then, they’re altered in the lab to fix a gene. Finally, they’re given back to the patient.

A recent gene therapy study at NIH successfully added a working copy of the hemoglobin gene into stem cells. Another study will see if adult cells can be altered to produce fetal hemoglobin.

If you’re living with sickle cell disease, talk with your health care provider to develop a care plan that’s right for you. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle can help you prevent or control some of its complications (see the Wise Choices box for tips).

If you’re interested in joining a clinical trial, call 1-800-411-1222 or visit www.clinicaltrials.gov.

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison

Building 31, Room 5B52

Bethesda, MD 20892-2094

nihnewsinhealth@od.nih.gov

Tel: 301-451-8224

Editor: Harrison Wein, Ph.D.

Managing Editor: Tianna Hicklin, Ph.D.

Illustrator: Alan Defibaugh

Attention Editors: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov.

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits.